Kerry Kirk to Darren Levine: “I know you are extremely busy with the recent SWAT officer shootings, so thank you for making time for this interview. I have been intrigued by the history of Krav Maga and your involvement in it and want to share some of your story with our readers.”

Kerry Kirk: How did you find Krav Maga?

Darren Levine: I didn’t really find Krav Maga—Krav Maga found me.

There was a delegation put together by a philanthropist, S. Daniel Abraham, who lived both in the US and in Israel. It was his vision to spread Krav Maga to everyone in the United States through synagogues, schools, churches and educational programs – to give a gift from Israel to the United States – because Israel has expertise in security and had developed a self-defense and training system.

He (Abraham) was amazed by Krav Maga and was a big supporter of the IDF. He believed introducing Krav Maga to the world would do for Israel what Tae Kwan Do did for South Korea—spur interest in the country and the culture – that it would be a great way for people to see that the Israeli government was doing good, productive things and cares about security worldwide.

So Abraham formed a delegation in 1981 and embarked on a tour through the US to find candidates to participate in a summer program. During that tour, they found people from the major cities, except Los Angeles. I was teaching at Heschel Day School in the PE program with a boxing and karate background, and the delegation found of me. Sometime in May or June they asked me to participate in the program. I became part of the delegation – that is how I made my way to Israel.

K: How old were you?

D: I was 21.

K: Describe your relationship with Imi. How did you meet him?

K: Describe your relationship with Imi. How did you meet him?

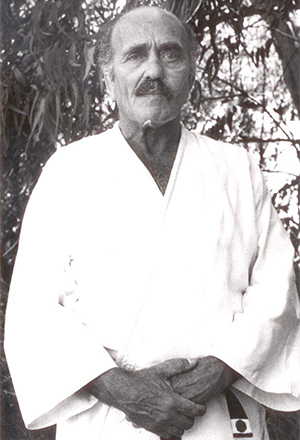

D: Imi did not do much physical training during that initial course. He would have been 71 years old at that time. But he did spend time with us and come and watch the training—making comments, corrections and giving instruction. He was meticulous about the teaching points he wanted us to understand – even if those points differed from the teachers who were giving the course. He was not shy about participating that way.

During training, we were sparring, but the equipment that was provided for the course was so bad. There was such a lack of safety equipment that our sparring had certain rules—the biggest rule was no punching or kicking to the head. I was fighting someone who was quite talented, and he kicked me in the head and then in the groin.

I ended up going to a doctor’s appointment the next day. What was surprising about this was Imi’s driver came and got me from the place we were training and said “Mr. Imi wants to take you to be examined.” I checked out perfectly fine, as I knew I would.

And you should know the training facility was in the bomb shelter of the Dream Beach Hotel in Netanya, Israel. The training was for 6-7 hours per day with a break and then more training at night – six days a week for six weeks – and I did an additional week.

After the exam at the doctor’s office, Imi took me to a coffee shop. At that coffee shop I was thinking that I needed to get back to the training. The town of Netanya is a pretty, Mediterranean town. Imi’s favorite coffee shop was called Ugati. He took me there around 10AM, and we did not leave until 5PM. At which time, he took me to his home, and I had dinner with his wife. Afterward, he escorted me back to my hotel.

The next morning, I was sitting in the cafeteria having breakfast, and Imi’s driver said Imi wanted me (and he was waiting outside). So I went outside, and he said, “I am taking you back to the doctor”, but I said I was fine and that the doctor told us I was fine. He said, “No, we are going to be sure you are fine.” So he took me to the doctor, and I was dying inside, because when you are doing concentrated training six hours per day a lot of material is covered – and I had already missed the entire second day. I did not want to miss any more and fall behind.

So, on the third day, he took me back to that same coffee shop and discussed the way he viewed Krav Maga, how he wanted it taught—he made points over and over again. I thought he was repeating himself, but he wasn’t repeating himself, he was communicating to me the very foundation of Krav Maga. I said to him at the end of the day, “Imi, I don’t mean to be disrespectful, but I have to go back and train.” And he leaned back in his seat, put his hand on his chin and pointed at me and said, “You are training right now.” And that was all he said, and he fell silent.

There was someone else sitting with us at that point, a sergeant major in the army who was in charge of Krav Maga training, who then said to me, “You have no idea how lucky you are right now to be sitting in that chair getting this kind of training.” And I started to realize that.

Then Imi gave me a fruit tray to take with me, because there was no food in the rooms where we were staying. So that was the beginning of the bonding. Imi even tried to get me to go with him the next day, but I said I had to get back to the training. He watched the training and there were other social events he attended, so he spent a lot of time with me. He was very interested in my family, my background.

K: How did that exchange program end? Did you become an instructor at that point?

D: At the end of the course, there were degrees awarded based on how each person tested, and not everyone tested very well. There were about three or four people who tested quite well, and each went into a small room with the instructors and with Imi. He (Imi) was sitting at a desk, and I sat across from him and received three diplomas. I received a belt diploma (the highest was green belt); I also received a diploma from the Krav Maga Association and a diploma from the Ministry of Education from Wingate University. All of those were teacher’s diplomas and spelled out what I could teach.

When Imi gave the diplomas to me, he said, “One day you will be responsible for running Krav Maga in the United States.” I didn’t question him aloud, but I was thinking, “What?” Then he said, “If you invite me to Los Angeles next summer, I make a jump to you.” (Imi’s term for flying across the world.) I was wondering as I left the training if he had made that offer to others as well—I didn’t know.

K: Did Imi ever make the jump to Los Angeles?

D: Before I left Israel, we exchanged phone numbers and kept in touch the entire year. Sure enough, he came and did a summer camp with me in Los Angeles for 4 weeks. Imi lived in my home, trained with me every day and with some of the top teachers you now know around the country – these people were between 10 and 12 years old at the time, like Michael Margolin, Marni, and John Pasqual. These people were all in that first summer camp learning Krav Maga from the Grand Master.

Imi also spent a lot of time with my parents that summer. We would get up early and go teach—summer camp was about 6 hours/day 6 days/week, and then Imi and I would train at night. We taught courses for adults and did demonstrations for law enforcement—now Imi is 72 at the time—it was quite an experience. I knew it was special at the time, but I didn’t know how incredibly special it was.

K: How did your relationship grow that summer–particularly with him staying at your family home?

D: Imi spent an inordinate amount of time with my mother and father. My mother (Shirley) was a renowned educator in Los Angeles and even toured the country. She was the principal of Heschel Day School. My father (Arnold) and Imi really hit it off. Imi adored my father—adored him, and my mother too.

Imi and my parents would talk late into the night – talking and often drinking champagne and eating strawberries until 2AM — no kidding! Imi would ask lots of questions about me, my brother, my sister, and my uncle, and cousins. He really wanted to immerse himself in the family, and he did. It was a great summer for all of us.

One of the side notes you should understand is that I never had a grandfather. Both of my grandfathers had passed away before I was born. Because Imi was with my family so much, and we spend a lot of time together, he became the grandfather I never had.

He was such a wise man, and he was so gentle in his way and so powerful in other ways – very debonair, very worldly. He loved dancing. We would go to Russian restaurants where there was dancing, and he would dance all night. The two of us would drink shots of vodka, and he would out drink me at 22–like it was nothing and still be dancing. He glided across the dance floor—everyone would watch him dance.

K: That sounds like an incredible summer. During that time, did you test for Imi?

D: During that summer in LA, Imi was preparing me for my blue belt test. We spent all of that time teaching together, training together, and he gave me the blue belt test – but halfway through, he stopped me and said, “You don’t pass.” He sat me down to talk, and I was really disappointed. It wasn’t the belt. I felt I disappointed him.

In any case, I did not pass the blue belt test. I was disappointed, and he said don’t be disappointed—“Blue belt in Krav Maga means you are a black belt in self defense.”

K: Were there other instructors that Imi included throughout your training?

D: Yes, the very next summer (1983) I went to Israel and trained with Eli Aviksar, Eyal Yanalov, and Sarge Barack who would end up being the Colonel in charge of all training of the Israeli army. In any case, I trained with Imi in a studio almost every day, and by now he is 73 years old. He was little by the way, very small, but so strong and knew exactly what to do with his weight. He was just incredible. He had amazing energy, balance and form.

D: Yes, the very next summer (1983) I went to Israel and trained with Eli Aviksar, Eyal Yanalov, and Sarge Barack who would end up being the Colonel in charge of all training of the Israeli army. In any case, I trained with Imi in a studio almost every day, and by now he is 73 years old. He was little by the way, very small, but so strong and knew exactly what to do with his weight. He was just incredible. He had amazing energy, balance and form.

K: Can you recall a specific time when you were training with Imi that sticks out in your mind?

D: I remember training with him in Israel–practicing cavaliers. I took him down with a cavalier, and I injured his shoulder. In my mind, I was so impressed with his physical presence, I felt I had to perform physically for him, and I really didn’t realize I was throwing around a 70+ year old man. The people who were protecting Imi said to me, “What were you thinking? You’re a young, strong kid throwing around a very old man.”

I felt badly. I told them, “When I was on the mat, he didn’t seem like an old man,” and they laughed because they understood what I meant. Imi kept saying things like “Take me! Take me! Do it! Do it!” I did, but I injured his shoulder accidently.

At the conclusion of that trip, he double tested me for blue and brown belt. I passed both the tests.

K: Imi was still practicing Krav well into his 70’s? He must have been quite the athlete.

He was. I believe he held the European and Czechoslovakian championships in wrestling, boxing and gymnastics–three different sports–at the age of 19.

Being a gymnast, a dancer, an acrobat, a boxer, and a wrestler, his whole life was about movement. He could gracefully transition from one movement to another to challenge one’s balance and strength and coordination. He designed Krav to get people to a high level of proficiency quickly.

He didn’t just develop the Krav Maga system for the Army, he also developed the entire tactical movement system – for instance, how to jump over walls and maintain a low profile. He thought very critically with elegant simplicity and practicality. Imi brought a tremendous amount to the table. He (Imi) didn’t want people to do more than what was necessary to hurt anyone – except on the battlefield. The battlefield was different.

He was a very humanistic person and very nonpolitical. He had that part of him that couldn’t stand politics even though his role within the military was, in some ways, so very political. Politics – it’s what really killed his spirit in the end.

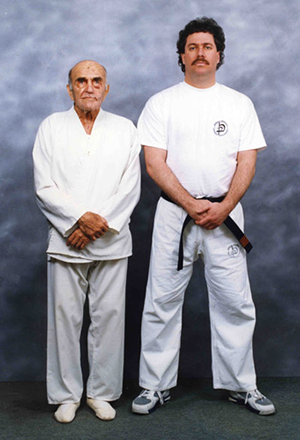

K: I have seen an old picture with you and Imi standing together and you are wearing a black belt and Imi is not wearing one. Is it true that he gave you his black belt?

K: I have seen an old picture with you and Imi standing together and you are wearing a black belt and Imi is not wearing one. Is it true that he gave you his black belt?

D: To be honest, I don’t recall if that was his black belt in that particular picture, but yes, the story is true. The year that I was awarded a black belt was special. I wasn’t expecting to test. In fact, that year when I went to Israel I worked mostly on reorganizing the Krav Maga system in terms of what techniques were included and where. Quite frankly, Eyal Yanilov and I developed much of the modern, published training. Our efforts were eventually published in a book that had the entire system in it. That took a lot of time and effort.

But going back to what you asked, I ended up testing and I passed my black belt examination. There were other people there to train, other people from the U.S. delegation who are still teaching Krav Maga and we were having a dinner before everyone was to fly back home. Imi disappeared for a while during the dinner. When he came back, he stood at the head of the table. He said some nice things about me, and then out of a pack, he pulled out his black belt and handed it down to me. He told me I had passed the test. He awarded me his black belt, it was not really black in color anymore; it was more like a white-gray belt because it had become so worn out over time. He passed his original belt on to me.

K: What was that moment like for you?

D: It didn’t seem very real, but I remember the reaction of Alex Feldman who was sitting near me. He said, “Can you believe what just happened to you?” Other Krav Maga instructors attending the dinner who had been with him for 20 or 30 years had never seen him make a gesture like that.

K: Did you go there most summers or every other year?

D: I would say either Imi came to me and we did courses here in the U.S. or Eli came here or Eyal came here, and I would go there. These were not 3-day trips, these were more like 4, 5, 6 week visits at a time – where all I was doing was training Krav Maga six days a week.

K: How many years did you travel to and from Israel?

D: Until Imi died in 1998.

K: That is an incredible series of events. I’d like to ask you about your founder’s diploma and how you earned it?

D: In the later years of Imi’s life, he was obsessed with finishing his book, and Eyal Yanilov really did the most work on that book, along with the publisher. I was in Israel, and basically all I did was spend time inside either my hotel room or Eyal Yanilov’s apartment rewriting the organization of the belt system and the training methods that Imi would approve. Eyal and I finished writing the book. Not without Imi’s input of course, because we would meet with Imi on every detail – and he would say, no, don’t say it like that, say it like this. I did much of the writing so it made sense in English.

You know I didn’t speak Hebrew and Imi didn’t speak Hebrew very well. He spoke a ton of languages, but did not speak Hebrew. We finally completed the book for the most part, and I hadn’t really trained all that much to be honest. I was just working on the book. It was non-stop writing and revision every day for that whole trip.

K: Okay. Did that contribution lead to you receiving a founder’s diploma?

D: That might have been a factor, but it happened later. Just before Imi died, there was a lot of infighting from people who wanted to be Imi’s successor. All of them fought for his attention. It was ugly. It was shameful. It was disgusting. There were just a few people who did not do this – who I will forever respect. Eli (Aviksar) left Krav Maga because of all the politics and started another organization. He never, ever pressured Imi for anything.

Anyway, I think Imi was toying with the idea of who would be left after he was gone with some degree of recognition–people, who in his mind, contributed most to the development of Krav Maga. So, he awarded Eyal and me the Founder’s Diplomas.

Interestingly, I don’t believe, by the way, that it was only going to be Eyal and myself. I think he was going to award a Founder’s Diploma to two other people. He just died before he could do that. I don’t know that Eyal would agree with that, but my impression is, based on a lot of conversations with him, that he was going to award one, possibly two other people, with that high recognition.

K: Imi sounds like a unique and thoughtful man.

D: Yeah, he was. In his apartment was a collection of knives. Every year, I tried to bring him a new special knife for his collection. He also had an impressive collection of African art, including spears and knives from Africa–really incredible pieces.

He explained how he came into possession of those. He was part of a delegation in the 1960s that traveled to Ethiopia to train their forces. Several people on that delegation ended up being Secretaries of Defense and Prime Ministers of Israel. Imi so impressed Haile Selassie who was the king of Ethiopia, that Selassie invited him stay in his summer palace. Haile Selassie gave him all these gifts—African masks, and other artifacts and was really very generous to him.

The generals and all the other people were staying in a little mini camp with tents and Imi was staying at the summer palace. It was really an odd situation. But that is just how Imi was. People were drawn to him.

K: Imi certainly seems to have had a magnetic personality. You have also said he was diligent and dedicated to training. Can you share a story that illustrates this?

D: Yes. Imi had his own room in his flat and under his bed, I swear, were thousands of pictures of Imi in boxes from photo shoots for manuals, for articles, for the Army, from the association, just thousands of pictures.

Toward the latter part of Imi’s life, we would sit on his bed and he would go through every picture with me. He would say to me in every picture you see this, this hand should not be here, the hand should be here, the foot should be here, not there – this is why this is a mistake, this is why we don’t do this anymore. We should be doing this now.

I mean he would do this for hours and hours and hours and hours. His physical skills had deteriorated but he was still such an amazing instructor through pictures. I remember thinking about these things and taking notes. I still have those notes – about those points that he stressed over and over again. We looked at probably a thousand pictures. There could be one picture that he spoke about for 10 minutes. Then he would say, hop up, I’ll show you, and he would demonstrate with me. You could write a whole article on just a single picture.

K: I knew you were close with Imi, but I didn’t realize how much time the two of you spent together. How would you characterize your relationship?

D: I was very close with Imi, and he used to say that as well. I realized early on in our relationship that when he would call me, I would be thinking to myself I haven’t heard from him in a week or so and right then, he would call. When I would call him, he would say I was just going to call you. I still remember his telephone number – 5336107.

We spoke and we argued and we were close. I think a lot of people were very jealous of our relationship, to be honest. When he stayed in our home, he said, “I feel like your home is my home.”

My parents were much younger than Imi, about 20 years younger. He said, “I know this is not going to make sense to anybody, but your parents I feel like they are my parents.” I never quite understood that, but he used to talk about their values and how they raised their children and their political beliefs. Their view of how we should live to make the world a better place. He truly loved them.

So when you say family, I feel he was family. I know he loved me. I know that. In some ways, I think he was almost closer with my parents. I think he loved me, because I came with the values and work ethic my parents gave me. That’s the best way to put it.

K: I don’t think anyone has ever questioned your work ethic, Darren—all nighters are not uncommon for you. So when did you know you wanted to do Krav Maga for your whole life? Did that just evolve or was there ever a light bulb moment for you?

D: I remember the moment perfectly. On my first trip in 1981, most people had dropped out of the initial course. There were people who had been chosen by the delegation that had no business being in this course – it was really demanding. I had experience playing football, I fought, did martial arts. But I thought the training in Israel was off the charts physically.

It was always “we’re going to teach these soft Americans” kind of thing. I remember taking photos of my mid section because it was so contused. I was purple and all shades of yellow and black.

They beat the shit out of us, and they didn’t have any equipment for us to use. The pads we punched were pillowcases stuffed with rags. Equipment wasn’t the priority at that time. We’re talking 1981–they were fighting wars.

K: Yes that would have been during the First Lebanon War. What a time to be travelling to Israel as a young man–and yet on that trip you knew Krav would always be part of your life?

D: Yeah–a few weeks into my first trip. I remember after one training session, we were pretty beat up. I remember standing out in front of our hotel room, which wasn’t far from the beach. I could hear the music playing, the Israeli music, and I loved Israel and I knew. It just came to me – I will never stop doing this. It was the thinking and logic behind the Krav Maga system; I felt like I was born to do it. I just knew at that time, 3 or 4 weeks into the training, that this was something I was always going to do. It was not even a question in my mind that it would be tremendously successful, because I knew I had a passion for it. I didn’t feel there was anything I couldn’t do, because I had that level of commitment.

By the way, I should say that when Imi was spending time with me, he was saying things to me like I can tell you will be an excellent instructor. I didn’t think much of it at the time, but after we had taught courses in the United States together, I did. I felt very comfortable, very natural explaining techniques and the Krav Maga logic behind them.

That’s what frustrates me today – all of these people who are teaching Krav Maga who don’t know how to think. If Imi could see what they’re doing with the name Krav Maga – seriously – he would roll over in his grave. He would cry because it’s the antithesis of Krav Maga that I see on the Internet on so many occasions. It’s the antithesis of doing the most simple and effective thing to eliminate danger, and it’s become more of a show that highlights things that would never work – and increases the danger for the very people we’re supposed give the skill of self-defense to.

It’s sad to me that there are very few people around the world who care about his dream and how much integrity he had – integrity as a person and integrity in terms of wanting to build a system that was effective. Now everybody calls what they are doing Krav Maga and truly it might as well be called some other system because it’s not Krav Maga – not what they’re teaching – not at all. I’m not saying this to criticize other people, I am saying this because Imi had such high integrity that he only included those things in the system that were battle tested.

Imi stressed simple movements, simple to learn, easy to remember under stress and if you didn’t understand him, and if he didn’t teach you how to think, you would not be able to analyze what you’re doing. You simply wouldn’t know if a technique is truly a part of the Krav Maga system. It’s a shame that somehow people think the fancier techniques get, the more…never mind. Can I tell a quick story?

K: Absolutely.

D: We went to a demonstration hosted by Dennis Hanover given in honor of Imi. Imi received an award, and all the top black belts were there. Dennis probably had 300 people there – smart people. They had Imi sit in the center on the mats watching the best people do a demonstration.

D: We went to a demonstration hosted by Dennis Hanover given in honor of Imi. Imi received an award, and all the top black belts were there. Dennis probably had 300 people there – smart people. They had Imi sit in the center on the mats watching the best people do a demonstration.

Someone did a knife defense and the guy blocked and grabbed the arm and took the person – kicked the person, kicked him in the head, took him down, spun around and stomped his head with the heel -and kicked him a few more times to the head- and then he jumped in the air and put the guy in an arm bar…to break his arm.

You know, everybody clapped. Then they asked Imi, what did he think of that technique. I knew it was coming. He said, “He’s a very talented boy.” This guy was between 30 and 40 years old who demonstrated. He’s a very talented boy. He called him a boy.

Well, what did that mean, he’s a talented boy? Imi didn’t want to lie, but they persisted. They said, “Well do you have any questions?” And Imi said, yes, I do. “Why did you break the arm of a dead man?” That was Imi.

K: Yes. I get it.

D: Why did you break the arm of a dead man? That’s what Krav Maga is becoming around the world. That thing he had…that he would make the comment to make a point in front of 300 people from a different system. And, he didn’t say a word until he was asked and pressed and finally he said what he thought.

My point is…that is how Imi thought. Most people don’t think like that. Some people who are calling themselves Krav Maga instructors are really doing crazy things like breaking the arms of dead people.

And they are making the same mistakes in other ways. They missed the whole point of the Krav Maga system. They missed it. It really does ruin the purity and the meaning. It’s just not in line with Krav Maga whatsoever. He wanted people to be able to defend and adapt with maximum speed and efficiency and power. That’s what he wanted.

Next month, look for Part 2 of this exclusive, two-part interview with Founder’s Diploma holder & U.S. Chief Instructor, Darren Levine.

Pingback: Kravology – Darren Levine Interview: Part 2

Pingback: Leadership | Kravology

Jeff

GREAT article and look into the life and founder of my favorite system. Thanks for sharing!