I was watching the CNBC program, The Profit, where a successful businessman goes into existing businesses and essentially does a turnaround. For these purposes, we’ll think of a turnaround as an intentional reversal of fortune.

The Profit, a man named Marcus Lemonis, takes failing businesses and creates profitable enterprises. If you watch the show, you know that Marcus believes strongly in basic business principles, cash flow analysis, and thoughtful investments that traditionally yield a return on the investment.

In the episode I’m referring to, Marcus meets a baker with a failing cupcake shop. The baker is ignorant about the most basic business principles and has borrowed money from his wife, mother, and a loan shark. Painful to watch… Throwing other peoples good money after bad.

On top of it all, the baker has signed another lease to open a second store, but his Alpha Site (his proof of concept, that is, his first store is failing). It becomes quickly clear that the baker wants/needs his business to revolve around himself. His identity is lost in his venture, and he’s forgotten about the customer in large part.

At one point, Marcus asks the baker what it costs him to make a cupcake. In short, the baker doesn’t know. Marcus asks the baker what his revenue and profit projections are going forward. He doesn’t know, doesn’t care, and doesn’t see the value in knowing. Ignorance is not bliss; it kills businesses.

The baker is lost in his vision of his stores, his baked goods, and his foolish, insistent way of doing things. This is entrepreneurial suicide. In the end, Marcus talks some sense into the hardheaded baker, and the store makes a great turnaround (tripling sales and reducing waste).

That’s the long way of saying I decided to ask the school owners out there, do you know how much it costs you to make a cupcake…I mean, sign-up a new member? If you don’t, read on. This is an exercise every business owner needs to be familiar with and comfortable doing.

There are a couple methods for calculating what a membership costs a school the moment it’s signed. For our purposes, we’re going to leave most of the overhead (rent, utilities, cleaning services, certifications, licensing, travel, contract labor, etc.) out of the process.

For some expenses, we’ll need to make reasonable estimates to satisfy a process called Activity-based Costing. This is a fancy way of saying we need to figure out what percent of salaries are spent focused on selling activity to account for this cost in the membership calculation.

The expenses we need to understand first are:

- Percent of salaries (time) dedicated to selling activity by position

- Commissions and bonuses

- Contract Labor used in selling activity (such as an introductory class)

- Insurance costs per student (usually paid per head)

- Credit card processing fees

- Advertising and/or marketing costs

This list, once complete, provides a window into what a martial arts school might consider Cost of Goods Sold (without allocations for large overhead costs).

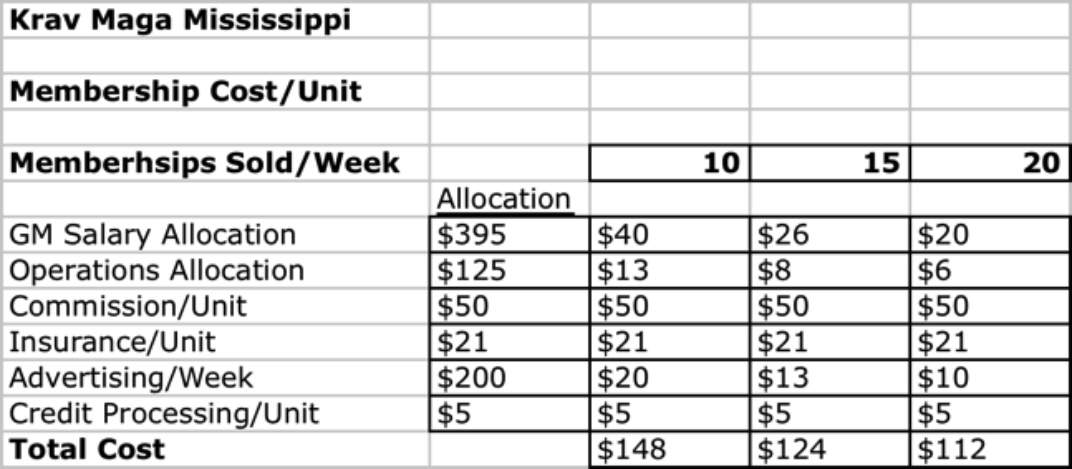

Consider the following scenario: Don’s school, Krav Maga Mississippi, is run by a General Manager who focuses 90% of her time on sales. An Operations Manager focuses 25% of his time on sales. Commissions, insurance cost per student, credit card processing fees, and advertising costs are all known and accessible.

Because Krav Maga Mississippi has a weekly introductory class, the numbers have been converted, when appropriate and applicable, to a weekly allocation. We now have the basic numbers needed to provide the baseline cost required to sign-up a new member.

Check out the graphic below:

What the graphic reveals is useful. If Krav Maga Mississippi sells 10 memberships per week, the cost per membership incurred by signing each new member is $148 each. By signing up just 5 more members per week, Krav Maga Mississippi can save $24 per membership sold – that’s a cost reduction approaching 20%. Conversely, if the owner of the school knows he’s charging a $99 enrollment fee, he’ll need to consider the value of losing $49 ($148 minus $99) every time he signs a new membership. Is this a good investment, given his monthly tuition, attrition rates, and cash flow position? How can the business owner redirect some of these expenses? Can he eliminate an expense or two?

The many business-focused questions that can be developed as a result of this simple analysis are very powerful. If you study the graphic, I’m sure you can develop a list of 10-15 “what-if” questions that could very well steer this business to greater success. Why not do the same for your business?

In any case, it’s clear that none of these decisions can be made confidently and intelligently without the data to support the analysis. So, get the data, do the analysis, and make data-driven decisions. Good luck!